What are programs and how are they different than projects and portfolios? Currently, there is a wealth of research and writing about project and project management. Even though project portfolio management also suffers from a dearth of publications, the conceptual relationship to financial portfolio management provides a solid underpinning of research. Plus, portfolio as a construct is more distinct than project and thus causes less misunderstanding. But programs somewhat caught between the realm of large projects and to a lesser extent project portfolios. Understanding program and hence program management is important for at least three reasons: 1) Undoubtedly programs are becoming more recognized as a distinct type of project work, the boundaries of this field need to be distinct. 2) As a discipline, program management gaining popularity as a mechanism of getting big and complex stuff done. A clear definition would encourage more studies and research, so the field can grow. 3) At a personal level, the obtaining a program management certification such as Project Management Institute’s Program Management Professional (PMI PgMP®) or Axelos’s MSP® Programme Management Certifications is seen as the next rational step in the growth of the project management career. For those who are preparing for the exam, it is important to develop the right mindset and perspective when thinking about program management and the associated exams. This article strives to clarify this important topic, and for a full length article, visit https://projectmanagement.co/blog/what-is-a-program/.

The most common definition of program is offered by the Project Management Institute. A program is defined as a group of “related projects, subsidiary programs, and program activities managed in a coordinated manner to obtain benefits not available from managing them individually.” (PMI Lexicon, 2020). The problem with this definition is that the term “related” is not defined. Is this relatedness based on shared resources, shared sponsorship and financial support, or something more such as dependencies of program objectives and benefits or projects within the program? The second part of the definition, “obtain benefits not available from managing them individually” is even more nebulous. After all, the entire field of management is about synergy and “doing more with less”. Worse, this definition can be readily confused with large projects, which arguably have work that can be organized as smaller projects with the larger project. On the other extreme, portfolio is also about a logical group of projects and other components too.

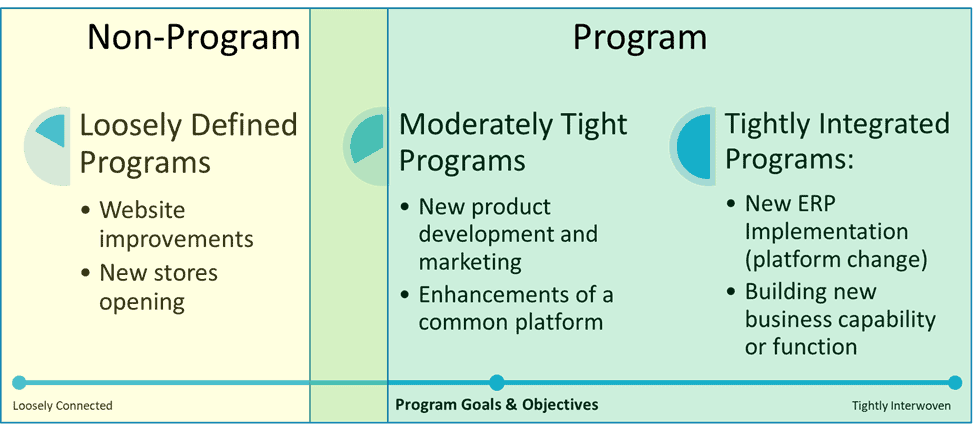

For this reason, Brian Williamson and I, in one of our latest publications, defined a program as “a collection of highly related components, such as sub-programs, projects, and other activities. When these highly related components are managed as a program, they can achieve great value and benefits not possible if they were managed separately.” (Williamson and Wu, 2019) We know, the definition not perfect too. But since publishing that definition, I thought about it more and came up with the concept of “program centrality” to place greater emphasis on the uniformity or centrality of purpose. In short, we are advocating that programs should have a program centrality that are toward the right side of Figure 1. It’s still a work in progress, but I believe to distinguish programs from large projects and portfolios, program centrality is important.

Program centrality is a measurement of the “tightness” of the components within a program, and it includes three important factors: relatedness, timeliness. and commonality of objectives.

- Relatedness – Examines the interconnection of the program components which includes projects and other activities within a project, program, or portfolio.

- Timeliness – Refers to the concerted effort and contiguous timeframe of implementation of these components.

- Centrality of Objectives – Describes how tightly integrated are the component’s objectives and their contribution toward the overall a program’s objectives and benefits.

Figure 1: Spectrum of Program Centrality

The table below describes these three factors for projects, programs, and portfolios:

| Concept | Projects | Program |

Portfolio |

| Relatedness |

Project activities and tasks are specific, and they are working toward achieving the agreed deliverables or outcomes.

A good practice is developing a WBS early on, where all capturing all the work that is required. |

Program activities are mainly reside in components, and there can be considerable dependencies among these activities. A significant part of the program management effort is to ensure integrated management of the work as defined in program charter.

The component work should be very interrelated to achieve a specific benefit. |

The work included can be related in any way that the portfolio owner chooses. Typical portfolios include work that are grouped by same resource pool, delivered to the same client, conducted in the same accounting period, or fit in a similar strategic group.

The work may span a variety of diverse initiatives, and these initiatives are largely independent. |

| Timeliness | Project have a definite start and end dates, and even in adaptive methods, the work is performed continually until its completion. |

Like projects, programs are temporary. There is an existence on a clearly defined beginning, a future endpoint, and a set of defined benefits to be achieved.

Comparatively, as programs contain multiple components, programs tend to have much longer durations. |

Portfolios are reviewed regularly for decision-making purposes but are not expected to be constrained to end on a specific date. Portfolios have life cycles, but they can be very long duration sometimes spanning across decades. Portfolios can be altered, ended, or merged with other portfolios based on business environment changes. |

| Centrality of Objective(s) | Project objectives are specific, often tangibly measurable. | In a tightly managed program, program objectives tend to be broader and measured as substantial benefits. These benefits are decomposed and become the primary outcomes of projects and other components within the program. The failure of one program component jeopardizes the entire program objective. | Portfolio objectives tend to be more loosely connected strategic objectives, often clustered in a common strategic group such as product families, business functional groups (e.g., IT portfolio), shared organizational objectives (e.g., revenue generation). |

In conclusion, the concept of program must be defined better, not only to distinguish from project and portfolio, but because the definition shapes how we view, understand, examine, learn, and expand knowledge. Programs are becoming more important unit of work as organizations tackle larger, more complex, more intertwined initiatives with higher stakes. For program management professionals, especially those who are pursuing program management certifications such as PMI’s Program Management Professional (PgMP) credential, it is even more important to develop the right mindset and perspective in both the application and the examination.

For a more detailed analysis of this topic, visit https://projectmanagement.co/blog/what-is-a-program/. This is an expanded article, also written by me, that contains more examples of programs and also finer category of distinctions between programs, portfolios, and projects.

References

PMI Lexicon of Project Management Terms (Lexicon, 2020). Project Management Institute, version 3.2. Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/pmbok-guide-standards/lexicon.

Williamson, B. and Wu, T. 2019. The Sensible Guide to Key Terminologies in Project Management, iExperi Press, Montclair, NJ. Glossary.

Note: PMI and PgMP are registered marks of the Project Management Institute, Inc. MSP is a registered trademark of AXELOS Limited.

Dr. Te Wu (PMP, PgMP, PfMP, PMI-RMP)

CEO, CPO

Prof. Dr. Te Wu is the CEO of PMO Advisory and a professor at China Europe International Business School and Montclair State University. Te is certified in Portfolio, Program, Project, and Risk Management. He is an active volunteer including serving on PMI’s Portfolio Management and Risk Management Core Teams and other roles. He is also a U.S. delegate on the ISO Technical Committee 258 for Project, Program and Portfolio Management. As a practitioner, executive, teacher, writer, and speaker, Dr. Wu enjoys sharing his knowledge and experiences and networking with other professionals.